Artiste : Iilian Miller

Titre : Diamond Mountains, Corée

Format : Oban

Signé : Hilian Miller, 1928 (à l'encre en bas à droite)

Date : 1928

15 3/8'' x 10 3/4''

Belle impression, couleur et état.

Artiste et graveur, Hilian Miller est né à Tokyo en 1895 d'un père diplomate Rainsford. Sa mère, professeur d'anglais, était venue au Japon pour une mission chrétienne. Lorsqu'elle était au Japon, elle portait des vêtements occidentaux, privilégiant souvent les cravates Amelia Earhart et les blazers masculins. Miller a ensuite passé une grande partie de sa vie d'adulte au Japon et en Corée, sur la côte ouest et à Hawaï. Aux États-Unis, elle s'est fait un nom avec ses gravures sur bois, découpées avec une précision minutieuse dans un style japonais hyper-traditionnel.

*Avec l'aimable autorisation d'atlasobscura.com, En souvenir de Lilian Miller, l'artiste pionnière de la gravure sur bois, coincée entre l'est et l'ouest. par Natasha Frost, 2017

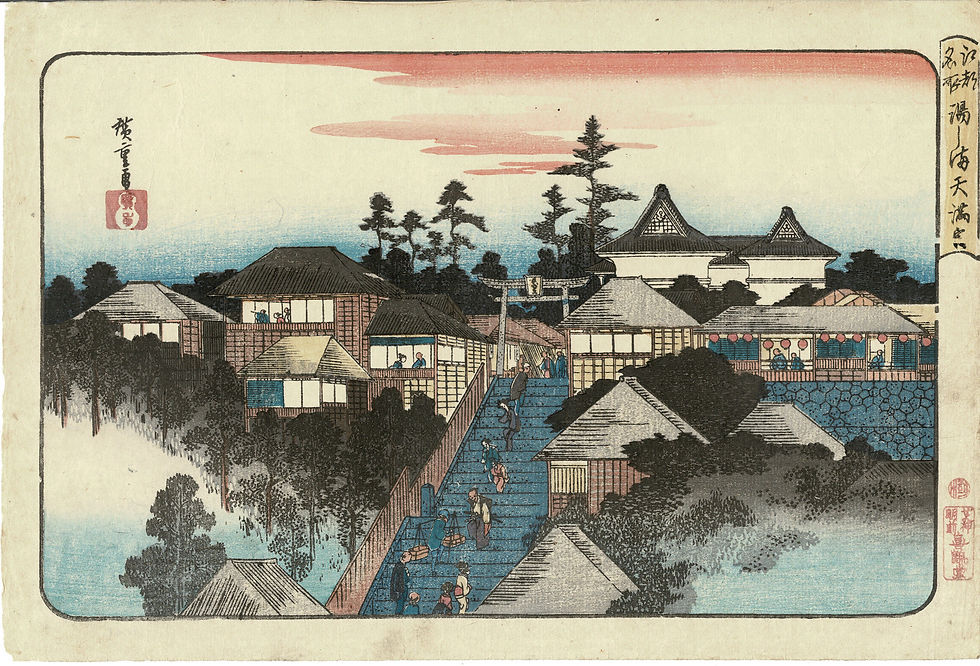

Iilian Miller - Diamond Mountains, Corée

Lillian Miller was a woodblock print artist, painter, and photographer born in Tokyo on July 20, 1895. The daughter of an American diplomat, Miller entered the ateliers of Kano Tomonobu and Shimada Bokusen, studying conservative brush painting styles until 1909. With a sudden turn of events, Miller’s father was recalled from his diplomatic mission, and Lillian would go on to Vassar College to complete her training in printmaking. After graduating in 1917, she took an extended vacation to Korea before returning to Japan two years later. Miller resumed her studies under Bokusen, and in 1920 her work, In a Korean Palace Garden, entered into Imperial Salon, whereby it was awarded the Tokusenjo or exceptional merit. From 1920 onward, Miller transitioned to screen paintings, loose prints, and woodblock-printed cards, working with carver Matsumoto and printer Nishimura Kumakichi II. Such works featured commercially viable images of Korean and Japanese figures and landscapes, marketed to Western diplomats and wealthy business people. After meeting Grace Nicholson, a purveyor of antique goods, Miller established a more robust network of patrons throughout the United States. In 1929 she returned to America and spent the year exhibiting in various museums throughout the country, resulting in significant commercial success.

Miller then returned to Japan, staging several exhibitions until 1935, when she developed ovarian cancer. Political instability the following year forced her to relocate to Hawaii, where she devoted herself to watercolors and Sumi-e. After two years, Miller once again relocated to San Francisco, where access to larger markets enabled her to continue selling prints. But in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Miller chose to put away her brushes and devote herself to the war effort, working as a Research Analyst for the U.S. Navy. In 1942, after discovering a malignant tumor in her abdomen, Miller was hospitalized and passed away the following year. The life and legacy of Lillian Miller are unique in many respects. Miller was the only Western artist of the early twentieth century born in Asia with a mastery of the Japanese language and cultural apparatus. Financially independent, self-carving, and self-publicized, she operated without domineering hanmoto publishers. Miller further transgressed the traditional sexual, economic, and social roles, remaining single and unmarried throughout her life.

Despite the heterodoxy of her activities, Miller's work was far from transgressive. Her lyrically naturalistic prints and watercolors of Japanese and Korean figures and landscapes parallel the romanticized views of Asia at the heart of Western discourse. In contrast to her Western contemporaries, Miller's prints were devoted to East Asia's quaint, traditional, and feminine aspects. She could adapt such knowledge of Japanese painting to Western palettes, evolving a style of her own, which was both fresh and individualistic. Furthermore, her success as an artist is, in many ways, attributed to bridging the gaps between both cultural and national identities.