Okumura Masanobu in "The Pillar Father", A Master of Movement Capturing a Shoki in Time, Space, and Heavy Black Lines

- Roland

- Jan 12, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2025

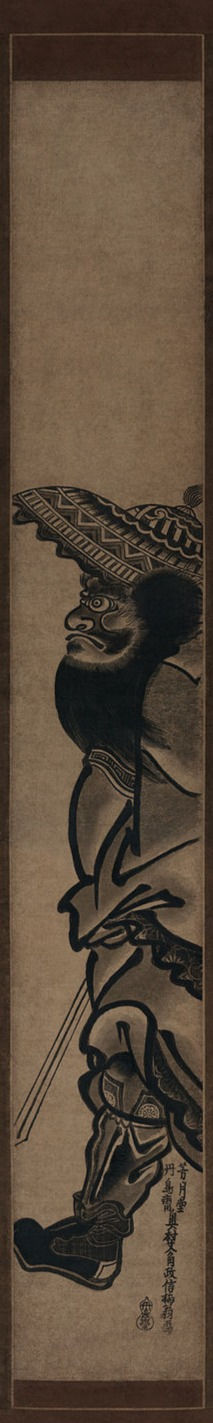

Right: Hashira-e (Japanese Pillar Print) depicting a Shoki by Okumura Masanobu from the Edo Gallery Collection

Okumura Masanobu, a legendary Japanese artist of the eighteenth century, is renowned for his masterpieces that depict various aspects of everyday life, history, and mythology. Among his many notable works is a captivating hashira-e titled “Shoki the Demon Queller.” This article explores the genius of Okumura Masanobu and delves into the significance of his portrayal of Shoki, the legendary figure who battled demons.

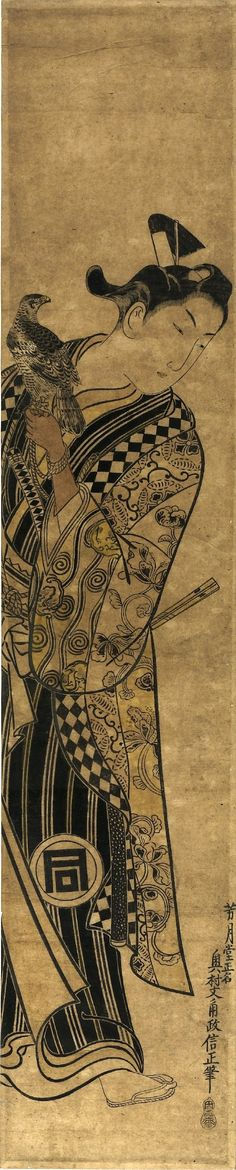

He is said to have been the inventor of the Japanese pillar print (Hashira-a) – a style of Japanese woodblock print popular during the Edo period. He gained considerable fame for his contributions to the development of the ukiyo-e genre, particularly his experimentation with new techniques and subject matter.

Born at the end of the 17th Century(1686 Japanese Edo period) Okumura Masanobu started his life during a time of great peace and prosperity for the island of Japan. Its citizens, at the onset of the Tokugawa rule, were cleansed of almost all Western influence after a violent purge of all things and people, especially those related to Catholicism. The purge left not a single surviving Westerner, Jesuit priest, or Japanese convert, a twenty-year genocide leaving a butcher’s bill estimated at around 50,000. By the year 1630, all contact with the outside world was limited to a single small island, bequeathed to the Dutch, tolerated simply because they did not push Christian teachings on the Japanese, the only Westerners smart enough to remain impartial to the fanaticism sweeping the kings and queens of the western world -an imperialistic rat race to conquer, and convert as many heathen souls and barbarian lands to Christianity. Vatican’s call to arms and the race between European nations and their

imperialistic dreams of establishing as many colonies as possible amongst the New World heathens. non-fanatical Catholics including a great deal of newly converted Japanese Christians, ruled by the Tokugawa Shogunate, were cast into society by the feudal ranking system favored by those who followed the heavily influenced Confucian schools of thought under the Buddhist religion.

It was due to this time of isolation and prosperity that the Japanese Samurai class and craftsmen flocked to Japanese cities. Art, literature, poetry, and theatre all thrived under this system. The wealthy samurai class needed items that signified their wealth and power, fueling an industry of craftsmen competing in their craft to produce everyday objects into masterpieces. Lacquer bottles, dishes, woodblock printing, swordsmiths, bottle makers, Jewelers, fashioning works of art out of the simplest of things.

While the handling of money was seen as beneath the samurai class, it became an inevitable part of everyday life, a necessity that granted a newfound power to the lower classes, evening the playing field between the ruling 5% samurai and the craftsman and merchant classes. Art and creativity thrived in the atmosphere of what the Japanese referred to as “the floating world”, the booming pleasure districts nurtured a rich Japanese culture, captured and portrayed in ukiyo-e by the famous Japanese woodblock print artists who pushed the boundaries of the printmaking artform, developing a way to mass produce their art and disseminate it to the masses. They created books, gossip papers, theatre promotions(surimono), Kabuki theatre plays, and depictions of famous beautiful bijin-ga and geishas, in addition to the famous landscapes by Hokusai and Hiroshige.

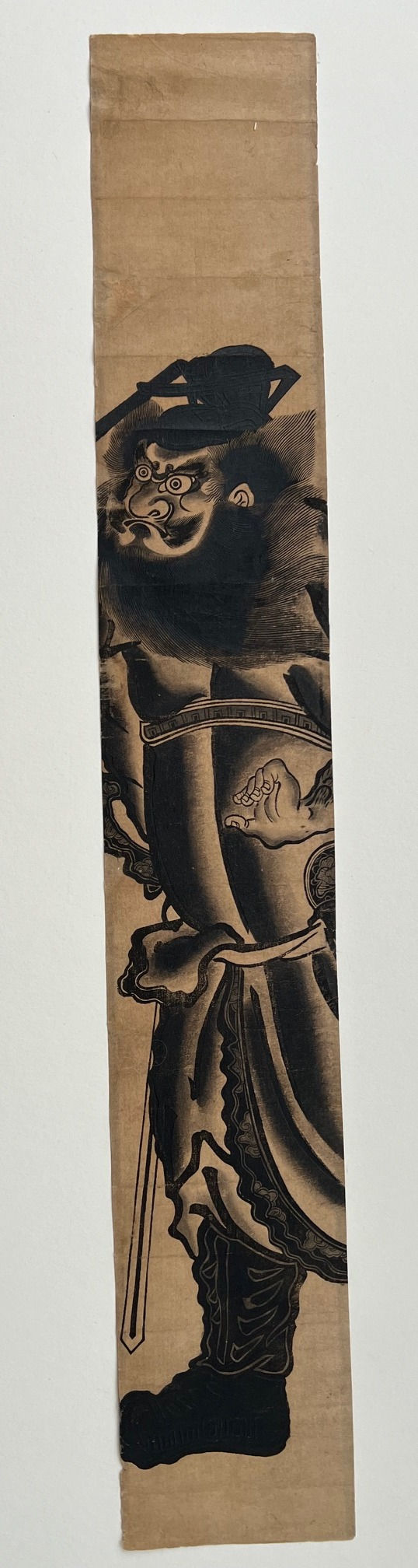

To the left: Shoki walking across the Pillar creates the illusion of catching a glimpse of the Shoki as if he were striding past an open doorway. (image from Wikipedia)

The woodblock print can be credited for helping to spread literacy amongst both the men and women population during the Edo period, which helped the Japanese usher in an industrial age rather quickly after the fall of the Shogunate. Masanobu, painter and publisher of illustrated books introduced innovations in woodblock printing and print-design technique in Japan.

Masanobu taught himself painting and print designs by studying the works of Torii Kiyonobu (died 1729), thus starting his career as Torii’s imitator. About 1724 Masanobu became a publisher of illustrated books and brought out his own works. He was one of the first to adopt a Western perspective through the Chinese prints available in Edo at that time. He produced large-scale prints depicting such scenes as the inside of theatres, stores, and sumptuous living quarters. Such prints were called uki-e (“looming picture”) prints for the foreshortening perspective effects they produced. He is also said to have founded the format of habahiro hashira-e, or wide, vertical prints. His style was noted for its vividness with gentle and graceful lines, which also showed restraint and dignity.

Okumura Masanobu executes the Shoki in the trademark urushi-e style of thick flowing black lines of which he is considered a master. He is also the first artist to begin experimenting with the hashira-e format. Pillar prints became massively popular during the Edo period, as the narrow format created interesting design characteristics for artists to explore. Sadly for us, this also means that intact examples of pillar prints are scarce, due to the fact that people actually decorated their homes with them.

“Shoki the Demon Queller,” often referred to as showcases Masanobu’s exceptional skills and creativity as an artist. The piece depicts Shoki, a mythological figure originating from Chinese folklore, who is known for his ability to ward off evil spirits and demons. Shoki is often depicted wearing elaborate garments, brandishing a sword, and possessing the strength to conquer any malevolent force.

Masanobu’s portrayal of Shoki in “Shoki the Demon Queller” follows the traditional iconography associated with the mythological figure. Shoki is depicted in a dynamic pose, as if captured mid-action, embodying his ability to move swiftly and protectively. The artist’s meticulous attention to detail is evident in the intricate rendering of Shoki’s intimidating facial expression, conveying both his courage and determination.

Moreover, Masanobu’s masterful use of movement in this woodblock print is truly captivating. He carefully manipulates lines and forms and creates a sense of dynamism. The flowing robes, cascading hair, and swirling clouds contribute to the composition’s energy, ultimately enhancing the viewer’s appreciation of Shoki’s heroic presence.

The choice to depict Shoki as the central focal point of the artwork exemplifies Masanobu’s artistic vision. By isolating and magnifying the figure of Shoki, the artist highlights his significance within the realms of Japanese folklore and mythology. Shoki’s role as the protector against evils and demons resonates with the popular belief in the Edo period that the piece was created, reflecting the societal need for supernatural guardians and heroes.

“Shoki the Demon Queller” showcases Masanobu’s technical prowess and mastery of woodblock printing. His skillful use of color, texture, and shading creates a visually stunning piece that is both aesthetically pleasing and thematically rich. The composition’s vibrant palette enhances the sense of drama and intensity, effectively conveying the eternal battle between good and evil, which Shoki embodies.

We highlight the significance of this particular artwork in the artist’s oeuvre. Not only does it serve as a masterpiece in its own right, but it also represents the artist’s ability to capture dynamic movement and convey timeless narratives through his works.

In conclusion, Okumura Masanobu’s artistic legacy continues to inspire and captivate audiences even centuries after his passing. Masanobu’s hashira-e (pillar prints) depicting “Shoki” remains an outstanding representation of his genius, showcasing his ability to infuse life and movement into his woodblock prints. His skillful portrayal of the Shoki executed with his trademark thick flowing black lines, captures the demon queller mid-stride frozen in space and time as if we are witnessing this legend stride past our bedroom door. within the confines of the narrow Japanese pillar.

To the right: Masanobu "The Father of the Japanese Pillar". The lines and Form are executed masterfully as well as Masanobu's use of the narrow confines of space inherent in hashira-e designs.

Comments